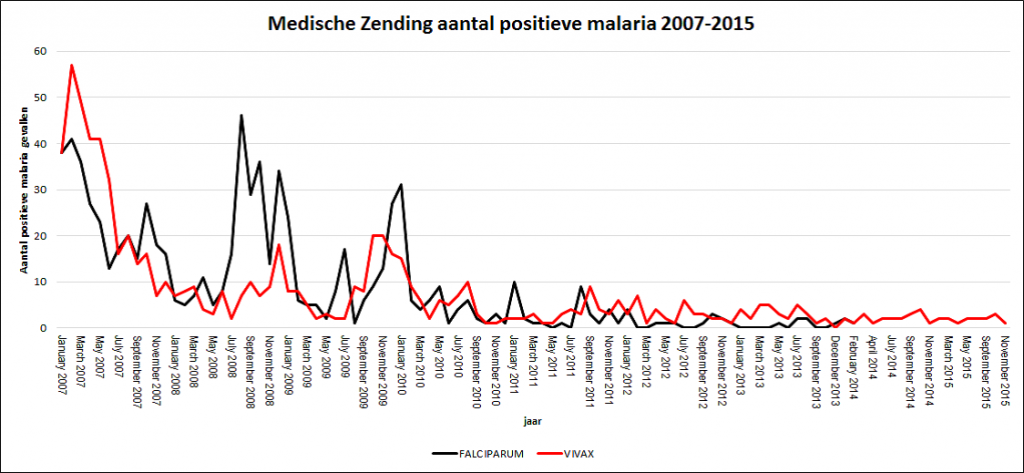

In the past, the interior of Suriname was a true source of malaria. The most malaria transmission in the Americas actually took place in Suriname. Today is World Malaria Day, a good time to reflect on the successes the country has achieved in recent years. Now Suriname has almost eliminated malaria. This means that the annual number of malaria patients has almost dropped to 1 patient per 1,000 people at risk. The goal is to be completely malaria-free in 2020.

Especially now that there is so little malaria in Suriname, there is work to be done. It is much more difficult to deal with the latest cases since they often occur far in the interior. In addition, it is more difficult to detect a few incidental cases. There is still a lot of malaria in the surrounding countries (French Guyana, Guyana and Brazil). Because people regularly cross borders, malaria still often passes the Surinamese border. For elimination, a difference is made between cases that occur in the country and imported cases. The import of malaria is a continuous threat for elimination. It can cause reintroduction into malaria-free areas. Areas with many (illegal) guest workers from the neighbouring countries are described as risk areas because of the cross-border activities of the population. These areas are in particular where gold is mined or where wood is cut.

The Surinamese malaria program tries to detect the latest cases by training people in these risk areas who can recognize malaria symptoms, perform a quick test and give medication. They communicate the results with the malaria program that also regularly visits. In addition, the program distributes insecticide-impregnated mosquito nets. Unfortunately, not many people sleep under a mosquito net in the risk areas. This is because it is too hot and there are few mosquitoes, but also for other reasons. One of the reasons given at the border, for example, is: “I want to be able to get out of the hammock as soon as possible when the police are looking for me, and not remove the mosquito net first”.

The sharp decline in malaria in the residential areas (villages) in the interior of Suriname. Source: Medische Zending

Voluntarily being bitten by mosquitoes

The malaria program works together with the Public Health Office (BOG), where I do an internship. The riskiest areas are visited every few months by the entomologist team of the BOG to look at the diversity and density of malaria mosquitoes. The diversity and density of malaria mosquitoes are determined by means of Human Landing Catches. For Human Landing Catches you try to catch as many mosquitoes as possible that land on your body in the middle of the night – when the malaria mosquitoes are active. This is a golden standard in malaria mosquito research and provides insight into the risk of disease transmission. Of course, there is a small chance that you yourself will get sick. The reason that this research may be carried out in Suriname is that malaria can be treated very well.

One of the top three risk areas for malaria in 2016 is along the Mozeskreek, where logging and processing company Greenheart is active. It is located in the middle of the interior, and relatively close to the neighbouring country Guyana. A lot of people from Guyana work at the company. Last year, an employee contracted Plasmodium vivax malaria in Guyana and took it to Suriname. This is a malaria type that can hide in the liver, and that can re-emerge if it is not treated properly. My colleagues and I went to this location for four days to perform the Human Landing Catches survey.

Road to Mozeskreek

It is Tuesday morning and I am waiting at the BOG with all my stuff for our four-day jungle trip. Mosquito traps ready? Check. Enough batteries? Check. Sugar and yeast for our attractant? Check. The chauffeur arrives along with my colleagues in a big pick-up car. Despite the large container at the back of the pick-up car, everything only just fits in. The items are neatly stacked under a large tarp. This way we can not lose our goods and they will remain dry.

We drive past the supermarket and make a little stop to buy some snacks and soft drinks. For seven hours, the red coloured bumpy road and the green tropical trees are all we see. Halfway through the route we accidentally made a sideslip. The road was muddier than expected and we end up off-road. Fortunately, the car has a four-wheel drive and with some help of a shovel and some pushing, we get back on the road (phew!).

Building up the study

Around half past five, we arrive at the location. We begin immediately with unpacking our stuff because at 6 o’clock the first evening shift starts. In addition to carrying out the previously mentioned Human Landing Catches, I also placed mosquito traps and ovitraps. Besides the BG-sentinel (see the previous blog), I also brought the Suna trap. The trap looks slightly different, but the operation method is the same. The Suna trap is specially designed for malaria mosquitoes. The BG-sentinel was designed for the yellow fever mosquito (Aedes aegypti). I’m curious about the kinds of species I can catch here, and what the catch differences between the traps will be.

Our personal luggage is put in our rooms and we check our mosquito nets for holes. Then I try to sleep as quickly as possible since I’m assigned for the first night shift.

The BG-Suna trap of Biogents at the open dining space of Greenheart. © Tessa Visser

Nightly jungle noises

Ten minutes before 12 I wake up and walk outside. I am immediately surrounded by a cacophony of sounds (listen to sound fragment). Instead of sleeping during the night, the whole jungle seems to be awake! You hear cicadas, frogs, birds and sometimes howler monkeys who can be heard from miles away, sitting in tall trees.

My colleague and I relieve the first team and sit down comfortably on a bench. We roll up our trouser legs make ourselves ready to catch mosquitoes with our suction tube and flashlight. Every hour we get up, we walk around and grab a cup of coffee or a peanut butter sandwich. To pass the time we have a lot of interesting conversations. In the middle of our shift, I see something special: “light beetles” (Lampyridae) as my colleague calls them. We do not know exactly what type. At the end of our shift, four malaria mosquitoes were caught. We quickly go to bed.

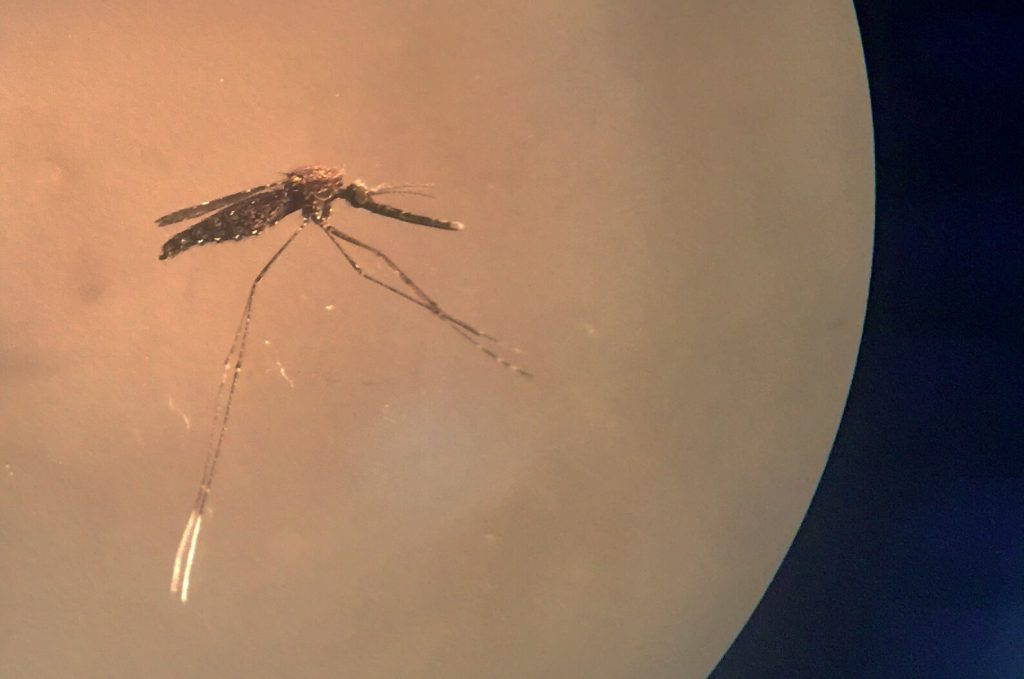

Determining mosquito species during breakfast

At 10 o’clock in the morning, we get together again for breakfast. We eat some scrambled eggs with tomatoes and “Guyanese bake”, a kind of savoury doughnut. Then look at the catch of the night under the microscope and determine the mosquito species. They all appear to be Anopheles darlingi, malaria mosquitoes that are very typical for tropical and wooded areas. They are very well distinguishable from other types of malaria mosquitoes due to the white ends of the hind legs.

One of the caught malaria mosquitoes under the microscope. It is an Anopheles darlingi female. © Tessa Visser

One of the caught malaria mosquitoes under the microscope. It is an Anopheles darlingi female. © Tessa Visser

Now there is a bit time left for relaxing! We drive to the beautiful Blanche Marie waterfalls. We quickly splash in the cool water and stay for an hour. Then we have to go back for the next shift…

At the end of our four-day jungle trip, the total catch by Human Landing Catches was 13 Anopheles darlingi. Unfortunately, the placed mosquito traps were empty and only caught a moth. Five Aedes eggs are found in one of the ovitraps. On the whole, the mosquito density at Mozeskreek does not seem to be high at the moment. This does not mean that there is no risk of disease transmission. Anopheles darlingi is known to be a very effective carrier of malaria even at low population densities. This is partly because this mosquito species loves to bite people instead of (forest) animals. Next week the results will be written down in a report and compared with previous expeditions.

For further information about the Surinamese malaria program, I would like to refer you to their website.

For further information about malaria research at Wageningen University & Research, I would like to refer you to the malaria dossier.

This blog post was originally written in Dutch for the Global One Health blog of Wageningen University & Research.

No Comments